Summary

We know that teacher and staff burnout and wellbeing are issues in Canadian K-12 schools. While we know the underlying causes of these issues is structural, there are open questions about whether organizational or individual interventions can help educators cope with this daily stress. In a 12 month research project, the Behavioural Insights Team undertook desk-based research and qualitative interviews to understand key barriers to educator wellbeing. Based on these barriers, BIT set out with the help of our partners to develop a light-touch, scalable intervention. As this is a new area of applied wellbeing and behavioural insights literature, we knew it was important to test our theory of change. We ran a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and our results are forthcoming in an academic publication. While we cannot share the detailed findings until the article is published, we did find a null result, meaning that the text messages (and principal emails) did not significantly effect burnout or wellbeing. As a result, we would not suggest an immediate scaling of the approach we tested. Instead, we would recommend the following ideas for further testing:

Introduction

Behavioural insights is an approach that uses evidence of the conscious and non-conscious drivers of human behaviour to address practical issues.[i] It is an approach inspired by the more nuanced and realistic understanding of human behaviour offered up by research in the behavioural sciences. Early applications of behavioural insights focused primarily on making small changes to how government services were structured and communicated. For example, a well known trial dramatically brought forward tax payments by informing late tax payers of the “descriptive social norm” that nine out of ten people pay their tax on time. In the decade since the phrase “behavioural insights” was coined, practitioners have started tackling increasingly complex challenges, like trying to find light-touch approaches to reduce burnout and increase workplace wellbeing.[1]

Work-related burnout and wellbeing have long been a focus of academics, practitioners and policymakers in education. Despite decades of research, there is a lack of clarity on what interventions work reliably and can be scaled beyond a single classroom or school.[ii] This report, which is aimed at educators and education researchers, outlines a recent initiative undertaken by the McConnell Foundation and Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), to develop, implement, and rigorously evaluate a scalable, low-cost solution to improve educator wellbeing in Canada.

[1] In one trial, 911 dispatchers received emails that encouraged a stronger sense of professional identity and a shared sense of community. Receiving the series of emails and accompanying stories led to a 39% reduction in burnout score on a validated scale. The intervention also reduced resignations by about 30% over a 6-month period, with no impact on sick leave taken.

The problem: Educator burnout and wellbeing

Educator burnout is a significant problem around the world, and Canada is no exception. As many as a third of teachers internationally identified as being stressed or extremely stressed.[iii] Similar levels of stress have also been identified amongst other school staff, including principals[iv] and vice principals.[v] A National Canadian Teacher Federation survey showed that 79% of teachers in Canada believe their stress related to work-life imbalance has increased in the last five years, with 85% of teachers reporting that work-life imbalance is negatively affecting their ability to teach.[vi]

Teacher burnout is associated with a number of negative health outcomes,[vii] increased absenteeism[viii] (which has knock-on effects for student performance),[ix] and lower job satisfaction/professional commitment.[x] The educational consequences of burnout include a diminished capacity to engage and teach effectively,[xi] poorer classroom climate and increased student stress levels,[xii] and worsened student behaviour and academic achievement. Staff wellbeing accounted for 8% of the variance in student standardized test scores in a 2007 study.[xiii]

Like burnout, school staff wellbeing has been associated with a range of both staff and educational outcomes including job satisfaction, teaching efficacy, and quality of classroom instruction.In particular, positive school staff wellbeing has been strongly associated with higher student wellbeing and lower levels of student psychological distress.[xiv]

Our initiative

The mental wellbeing of children in Canadian schools has become a growing concern, but it is not just children’s wellbeing that should concern us.[xv] [xvi] [xvii] [xviii] [xix]

Burnout and wellbeing are largely systemic issues, with root causes including managing difficult students, high workload, lack of support from management [xx], large class sizes [xxi], an imbalance between teaching demands and resources [xxii], and parent engagement.[xxiii] While a breadth of empirical evidence has been published on ways to increase student wellbeing, there has been little empirical research on how to address whole school wellbeing, including that of principals, teachers and non-teaching staff.

Based on this gap in the literature, BIT was engaged by WellAhead to create and test organizational approaches to improve school wellbeing in Canada. WellAhead is a McConnell Foundation initiative focused on integrating social and emotional wellbeing into K-12 education. To develop organizational approaches, BIT conducted exploratory research including a literature review of current wellbeing and burnout initiatives, qualitative interviews with educators in Canada, and interviews with leading academics. These activities grounded the project in the best available evidence and the lived experience of Canadian educators. Following this exploratory research, BIT and WellAhead, with continued input from a range of Canadian educators, developed two low-cost, scalable approaches for evaluation in a randomized controlled trial.

Schools from British Columbia, Manitoba and Alberta were invited to participate in the trial. A total of 2,178 school staff responded to our invitation and completed our baseline survey, and 1,217 of them (from three Canadian provinces, five school districts, and 109 schools) consented to participate in the study.

Exploratory research findings: Stressors & enabling factors for workplace wellbeing

Before designing an intervention to address burnout in the Canadian education system, we first needed to better understand some of the unique factors contributing to burnout and wellbeing amongst Canadian educators. To do this, BIT conducted:

- A desk-based review of the literature on wellbeing, burnout, and school culture change;

- Fieldwork in Vancouver, BC which included 25 qualitative interviews with principals/administrators (10), teaching and non-teaching staff (13) and school districts (2); and

- Consultation with 5 leading academics and 3 organizations specializing in wellbeing in Canada.

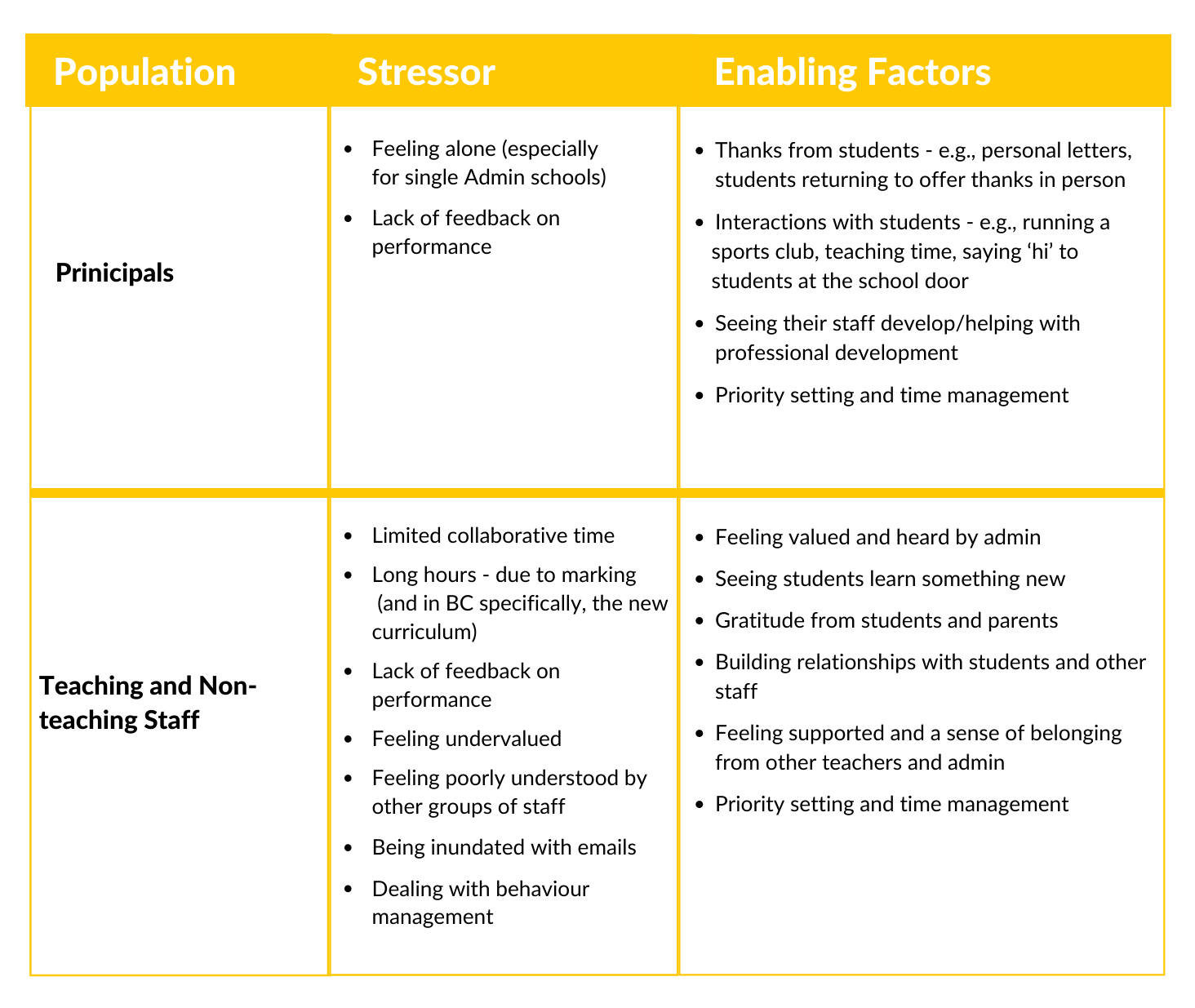

Our work uncovered some consistent themes, summarized in the table below. Stressors are defined as factors that decrease wellbeing and increase burnout, while enabling factors can help protect against burnout and improve wellbeing:

Intervention development

Equipped with a more comprehensive understanding of the factors leading to burnout in Canada, BIT reviewed the existing literature for well-evidenced solutions to increase the wellbeing of whole school systems.

From these interventions and our qualitative findings, BIT developed a number of potential intervention ideas for increasing wellbeing in schools. These interventions are based on principles from behavioural science and positive psychology. We aimed to identify and develop light-touch, low-cost interventions that have the potential to be feasible, impactful, and scalable. Ten promising solutions are listed below, with a notation regarding BIT’s perception of their potential impact and feasibility:

Outline of intervention

Ultimately, BIT and WellAhead decided on a light-touch intervention sending weekly text messages[xxiv] and leadership emails to participants. This approach enabled BIT to include several of the potential solutions listed above in a low-cost, scalable way. The aim of these messages was to bring attention to the importance of burnout and wellbeing, to communicate school leadership recognition of their importance, and, most significantly, to equip educators with evidence-based practices to enhance their wellbeing. We recognized that these weekly text messages and leadership emails would not address the root cause, systematic barriers to wellbeing. However, we believe that there was still significant potential and value in this more individually-focused intervention, given the severity of the challenge and need for multi-pronged solutions.

Development of text messages & principal emails

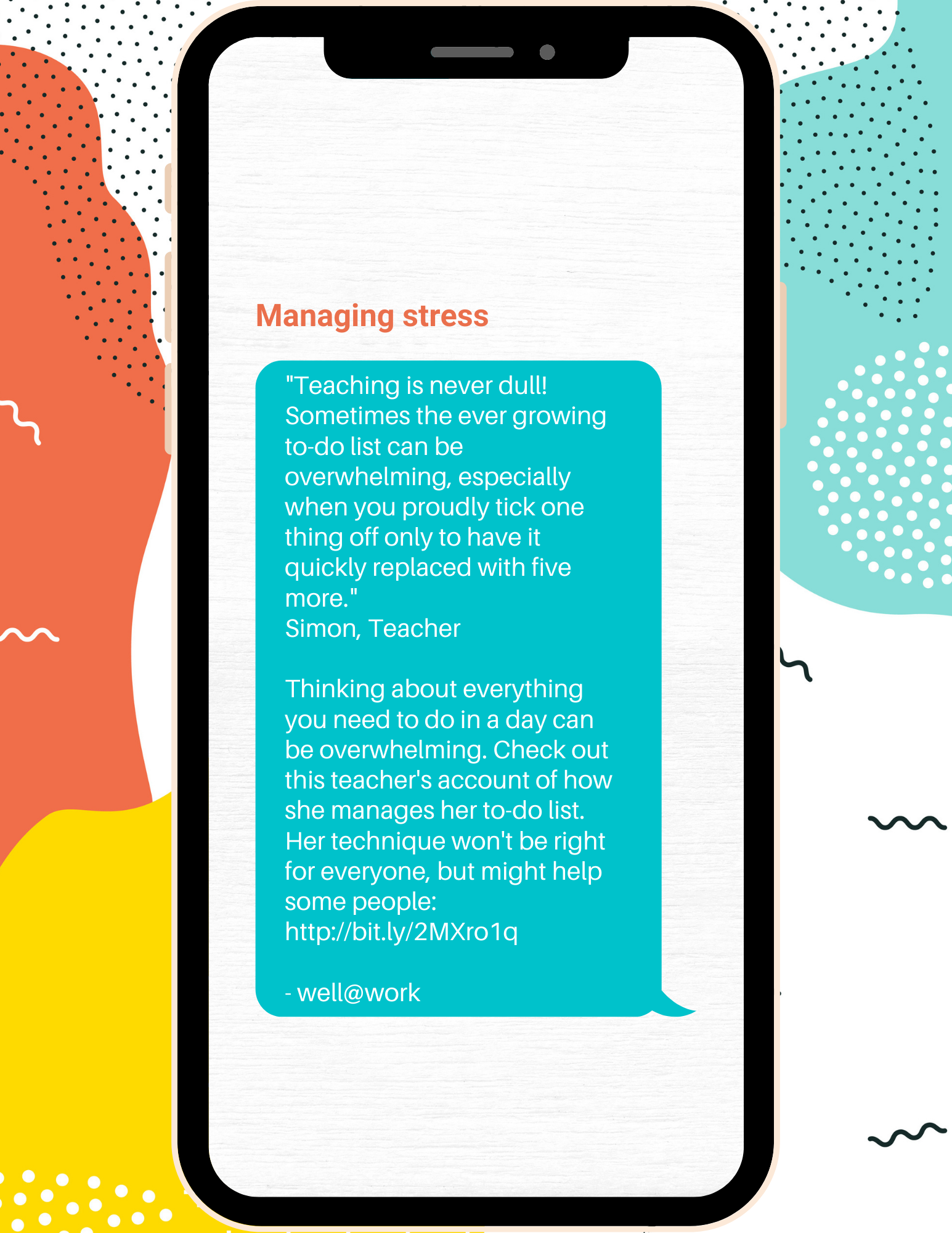

To develop the content of the text messages, our team reviewed relevant behavioural science literature, with a particular focus on positive psychology. Based on our review, we chose 12 themes which showed the most empirical evidence towards promoting wellbeing and preventing burnout:

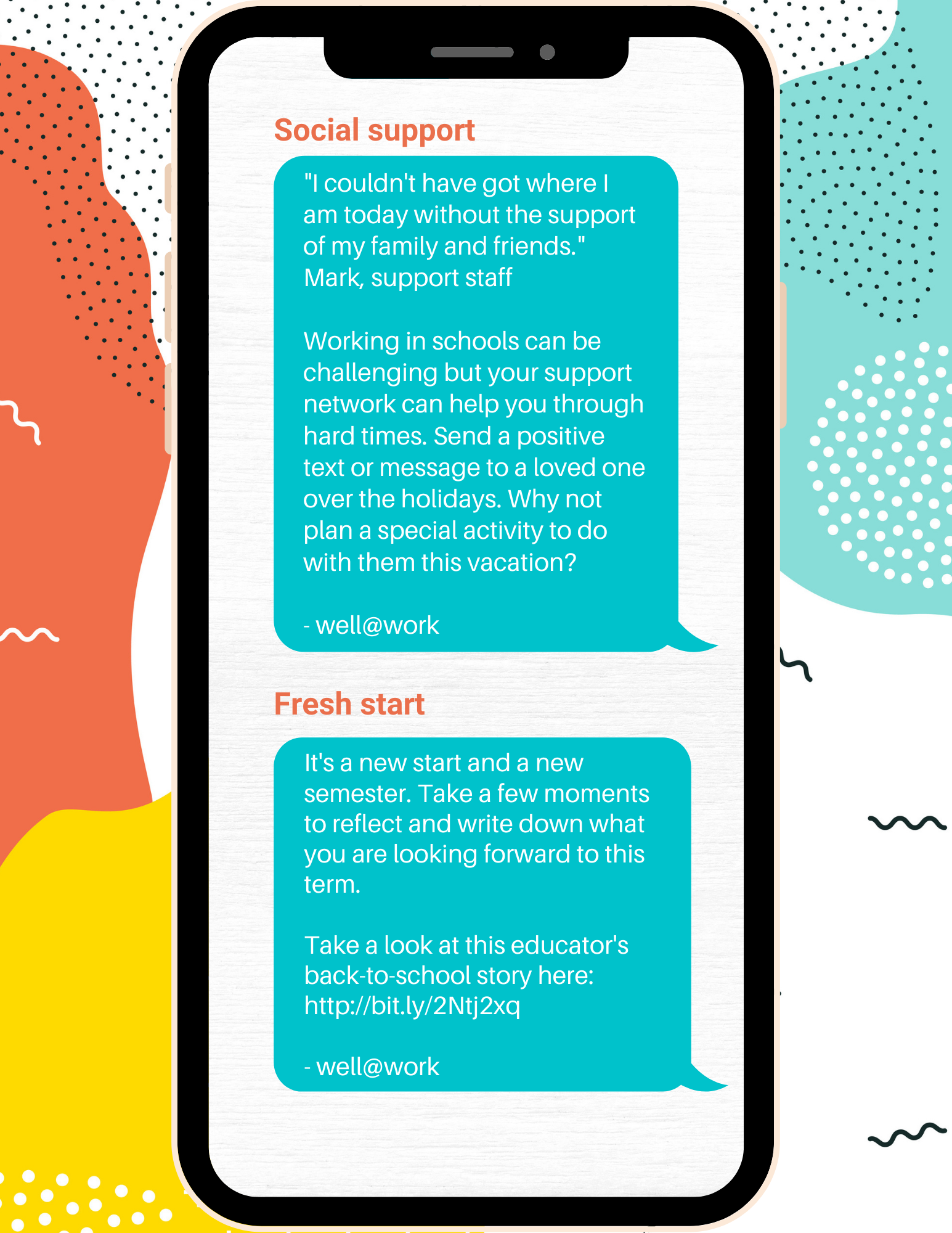

1. Fresh start effect

The fresh start effect is “the energy and determination we feel when we’re able to wipe the slate clean.” [xxv] Research has found this approach can help us refocus and distance ourselves from past failures.[xxvi]

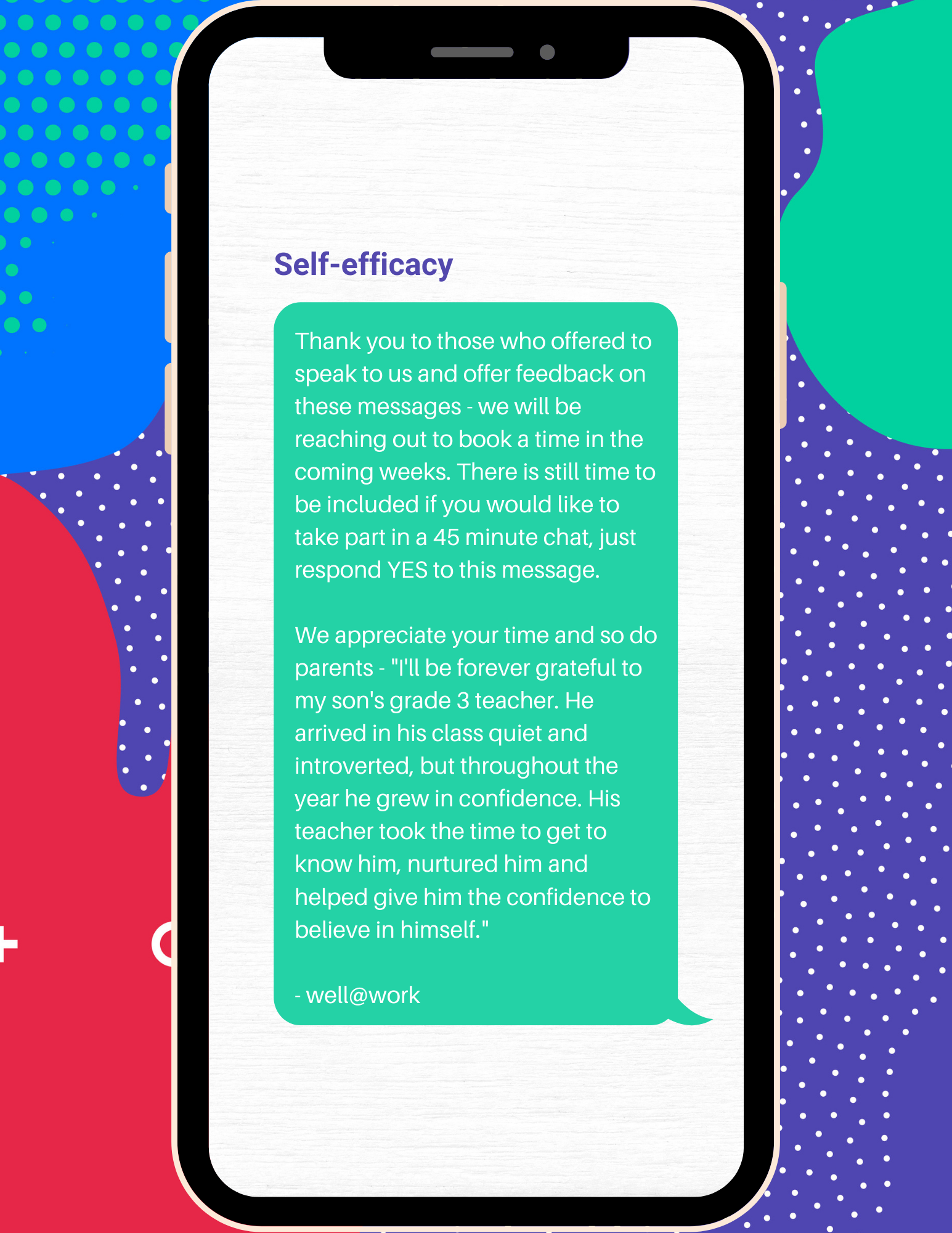

2. Gratitude from beneficiaries

Receiving gratitude refers to thanks from those whom you have helped (e.g., parents, students, other teachers). Receiving gratitude has been proven to increase individual motivation and engagement in positive behaviour. [xxvii]

3. Implementation intentions

Implementation intentions are exercises that specify when, where, and how a person intends to complete a goal. Different types of implementation intentions include barrier management, planning where/when/how, if-then plans, and action and coping plans.[xxviii]

4. Expressing gratitude

Expressing gratitude refers to showing thanks or appreciation. Gratitude expressions can increase prosocial behaviour towards a third party. By signalling to individuals that their efforts are valued, gratitude expressions may make them more inclined to help others.[xxix] Taking the time to be grateful for the positives in one’s own life can also boost wellbeing and improve the ability to cope with stressful situations.[xxx]

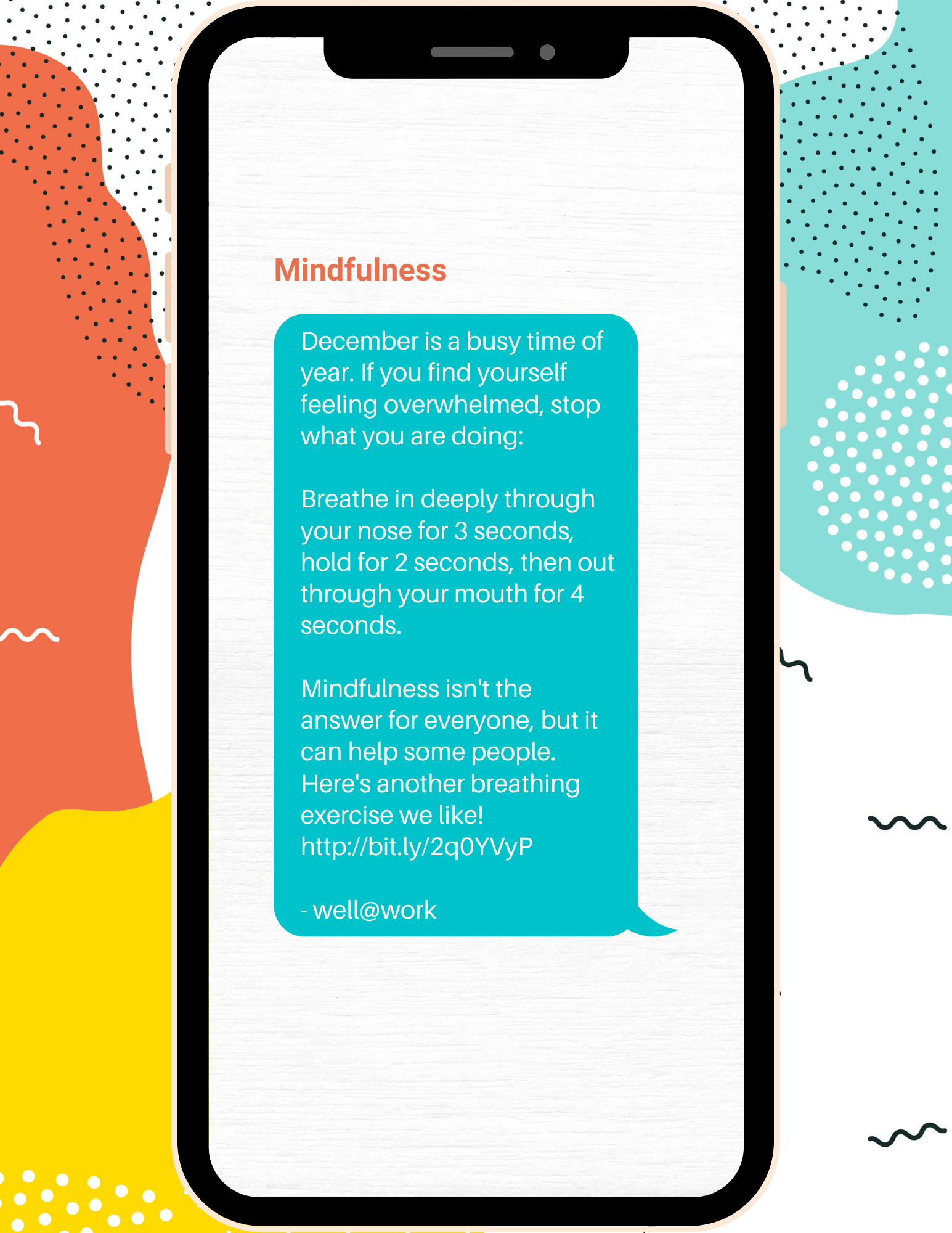

5. Mindfulness

Mindfulness aims to bring greater attention and awareness to the present moment. Regular practice is associated with lower emotional exhaustion at work[xxxi], as well as higher wellbeing.[xxxii]

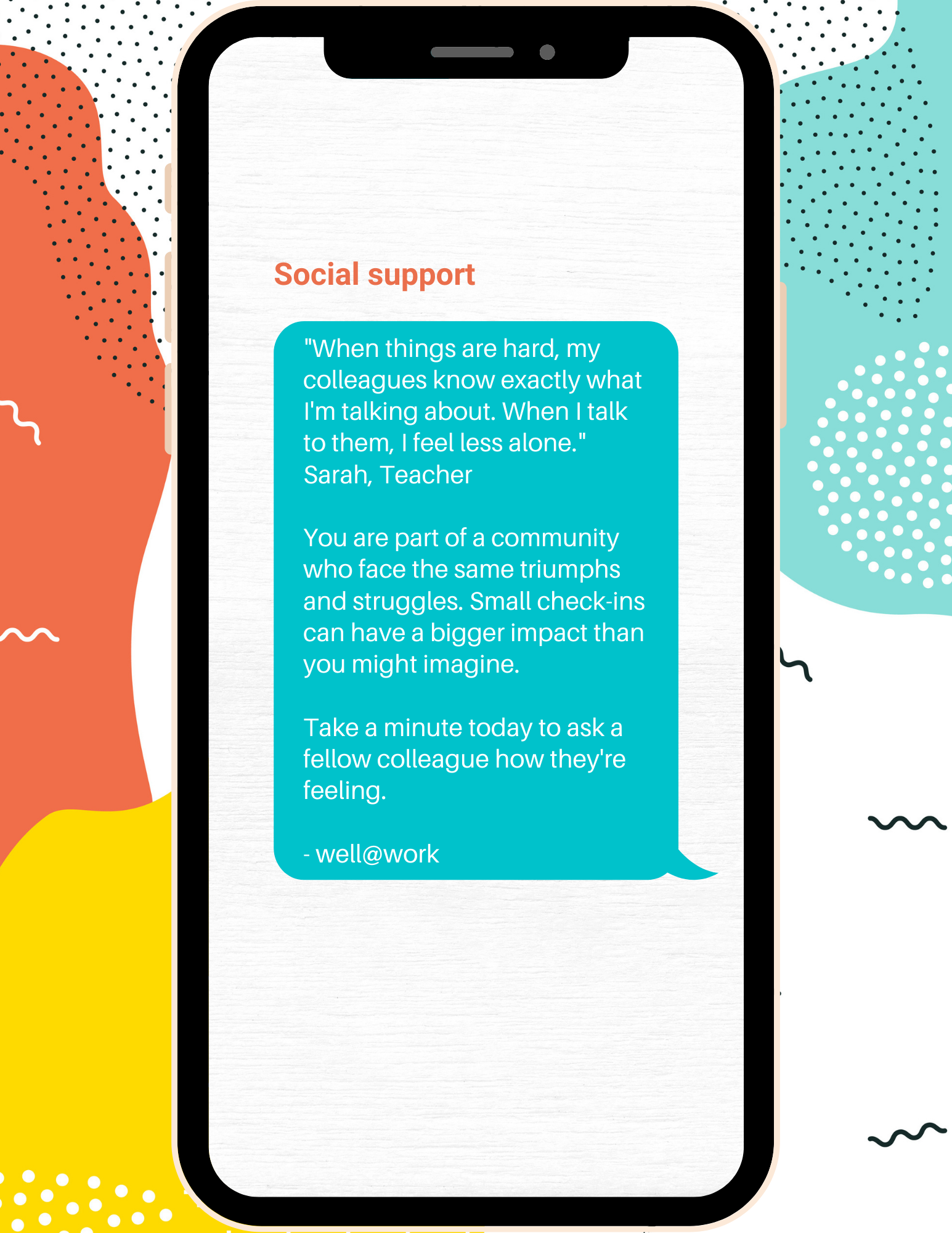

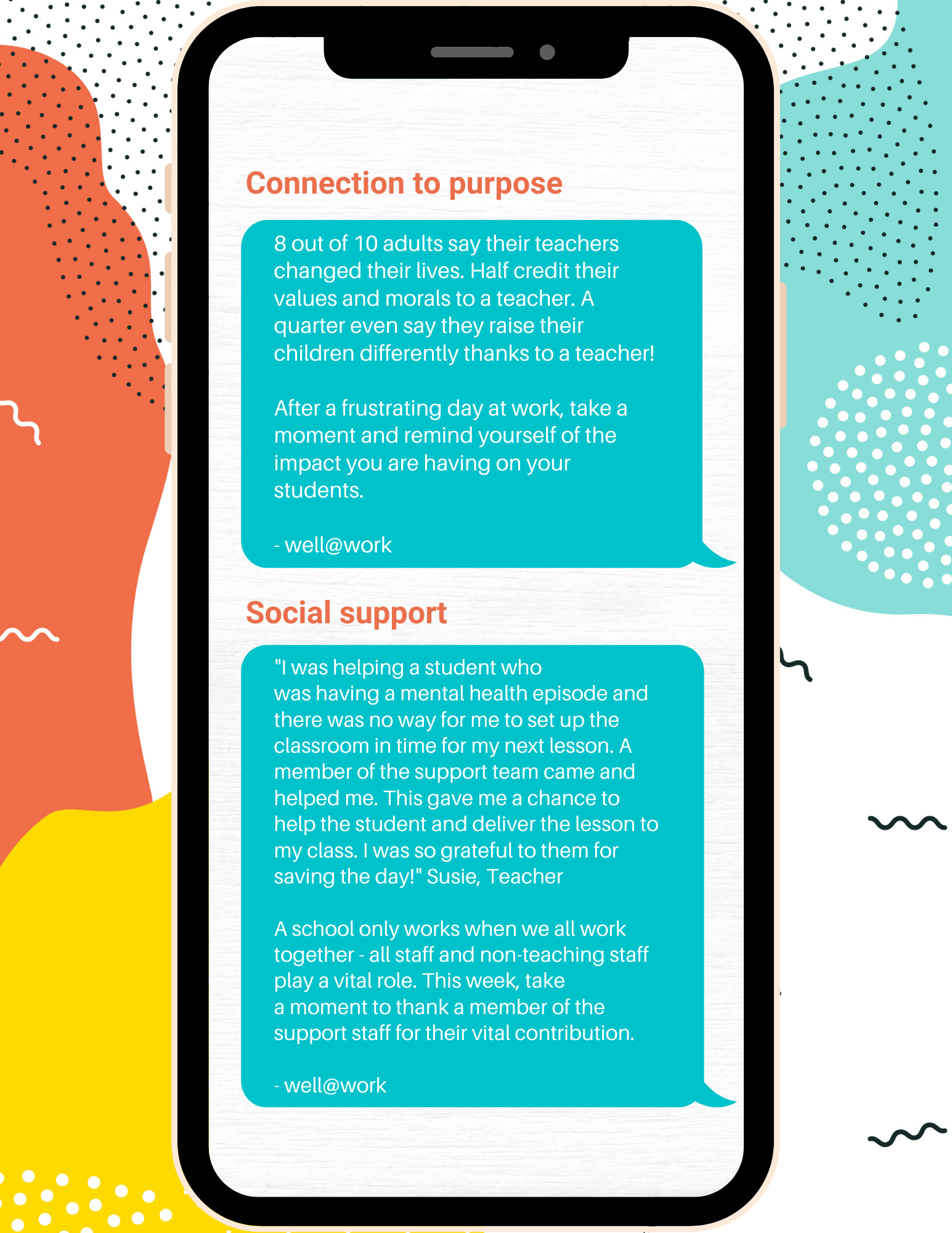

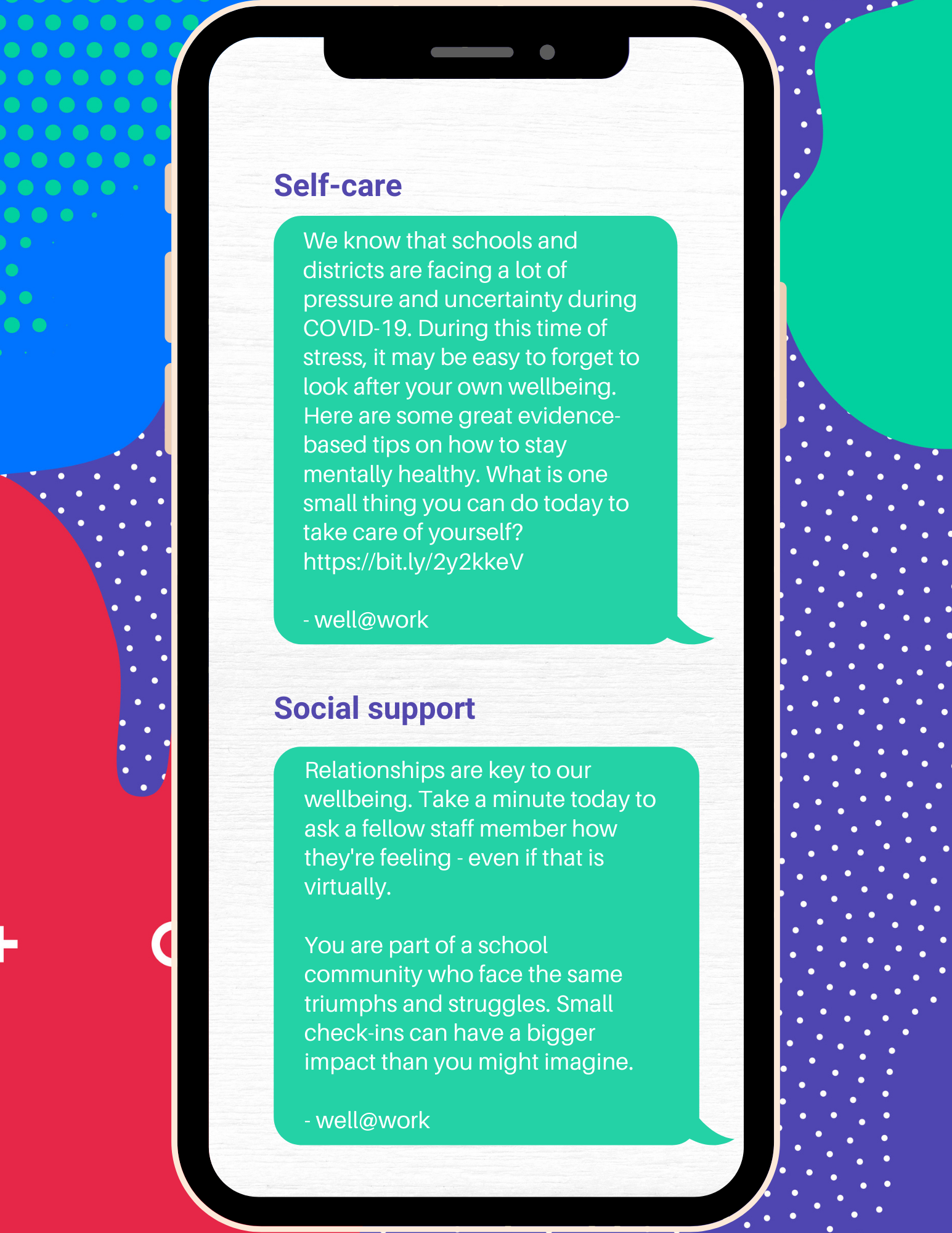

6. Social support

Social support refers to the social resources that people can access.[xxxiii] Research has repeatedly found that having good friends at work can buffer against negative life events and increase workplace satisfaction.

7. Connection to purpose

Feeling connected to the purpose of your work can help people behave differently. Research has shown that a sense of purpose is correlated with increased job satisfaction and organizational commitment.[xxxiv] [xxxv]

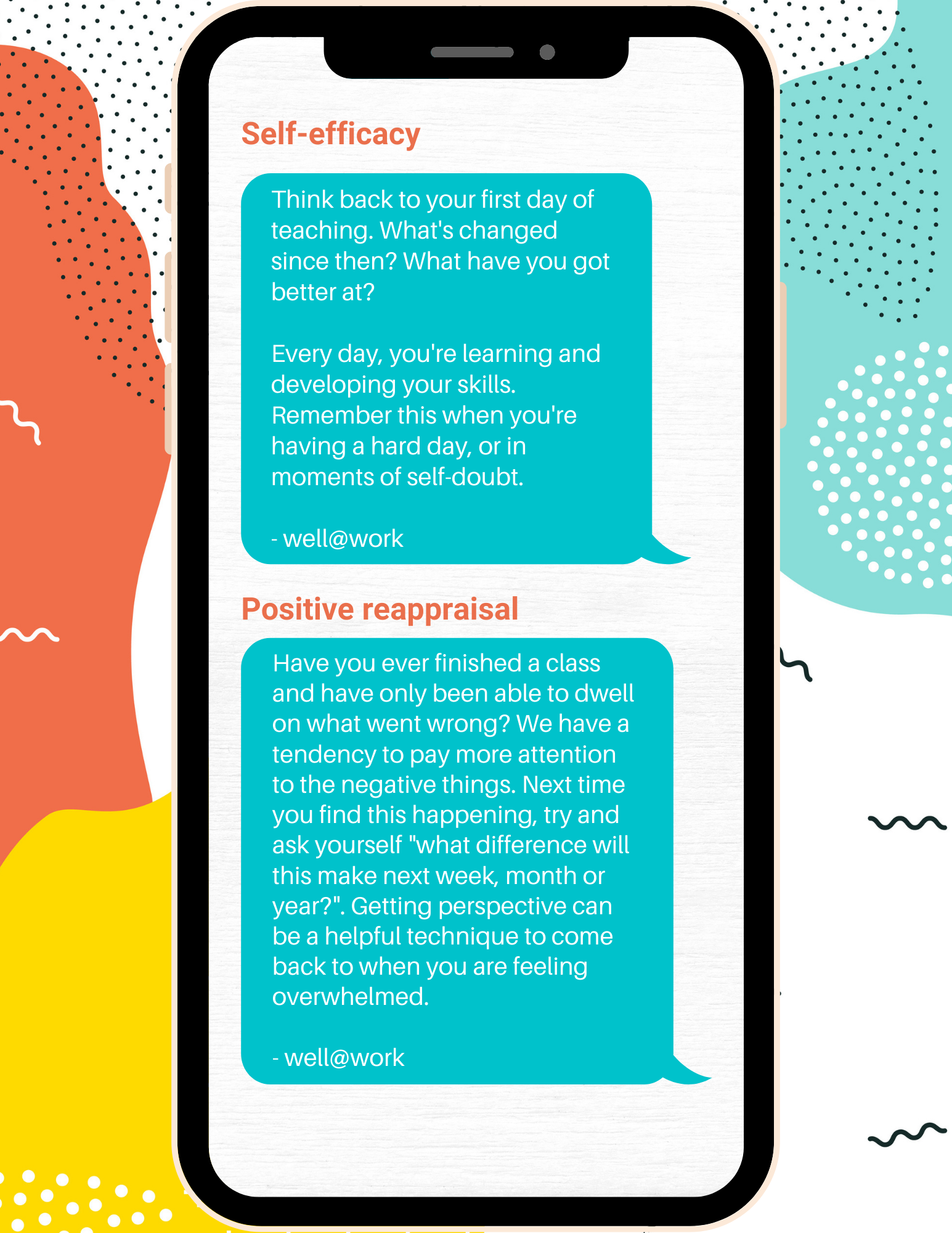

8. Positive reappraisal

It is possible to re-construe stressful events as benign, beneficial and/or meaningful.[xxxvi] Research has shown that such positive reappraisals can yield improved moods in response to stressful daily events.

9. Sharing meaningful stories

Narratives can help people make sense of our experiences and events and can encourage new ways of thinking about or seeing the world. Research has shown that sharing meaningful stories can motivate positive behavioural changes and reduce burnout.[xxxvii]

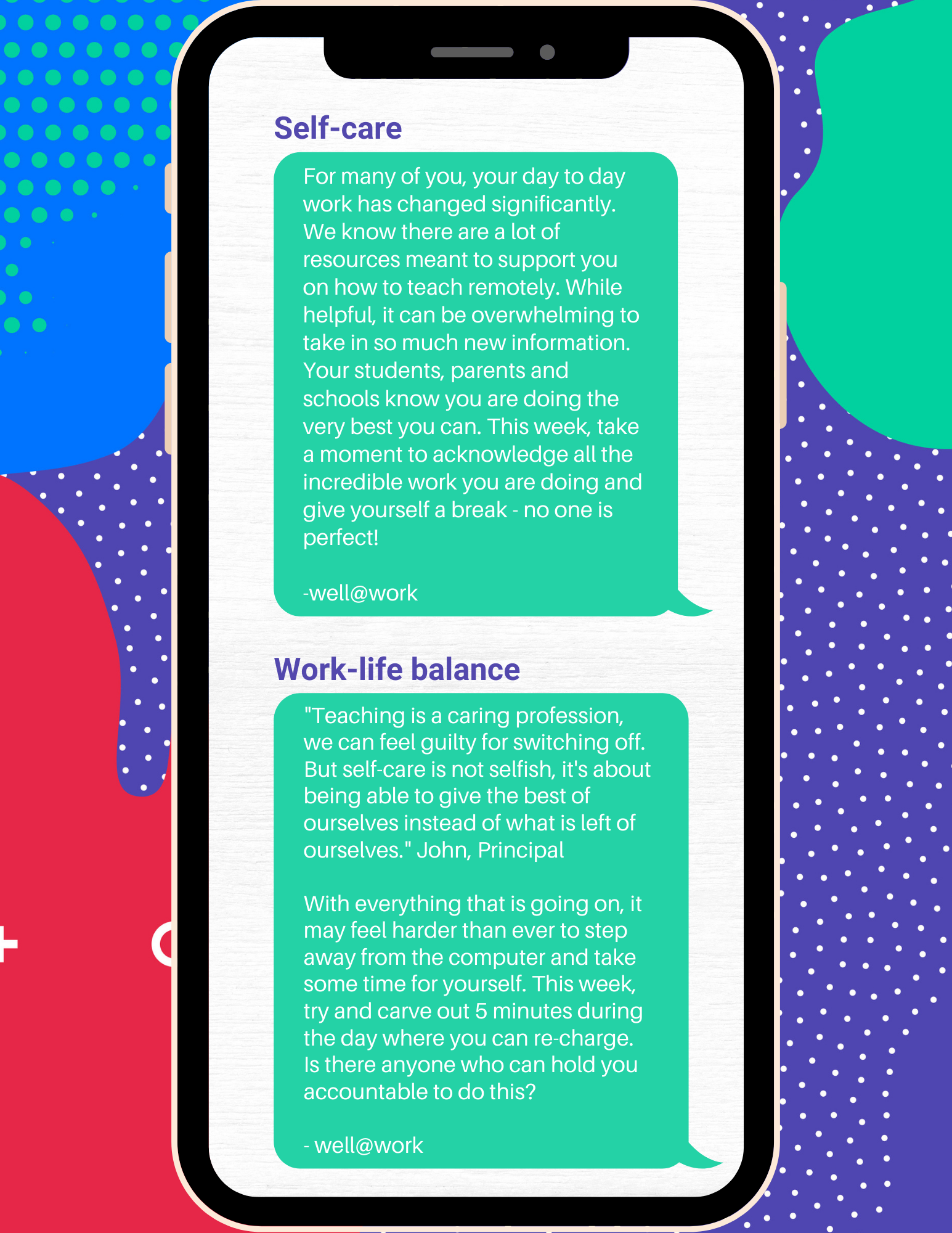

10. Self-care

Self-care can be interpreted in a variety of ways, from self-compassion to psychical activity. Research highlights the importance of teaching educators the importance of self-care as a way to reduce burnout and teacher attrition.[xxxviii]

11. Switching-off

Separating work and home life is essential for wellbeing and stress prevention.[xxxix] [xl] Research has shown that being able to ‘switch off’ after work has a positive impact on peoples’ lives.[xli]

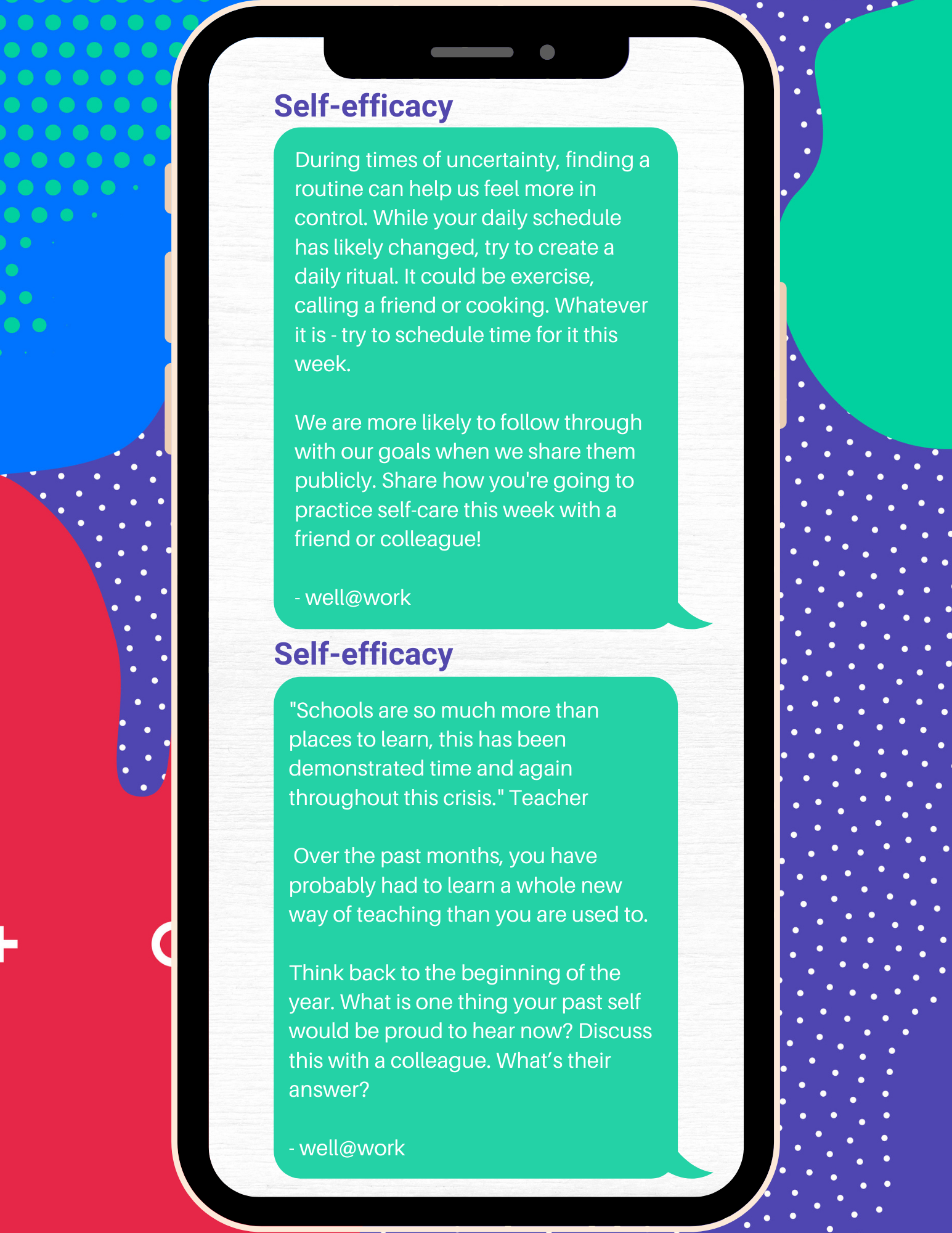

12. Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to the feeling of ownership over our lives and our ability to navigate day-to-day challenges. Research has shown that self-efficacy can moderate the relationship between work and stress.

We took these evidence-based concepts and created three separate schedules of text messages (SMS) tailored for teachers, principals and support staff, respectively. Once developed, we piloted these messages with a group of teachers, principals and support staff to ensure we were striking the right tone and messages were appropriate.

Similar to the development of the text messages, BIT chose four evidence-based concepts (1) wellbeing endorsement; (2)fresh start; (3) mental health support during COVID-19; and (4) gratitude as the basis for the principal emails. During our exploratory analysis education consultations emphasized that authenticity of these emails was key. If the emails didn’t match the context of the school culture, there could be a backfire effect. Therefore, along with email templates, we included recommendations on how principals could tailor and personalize them.

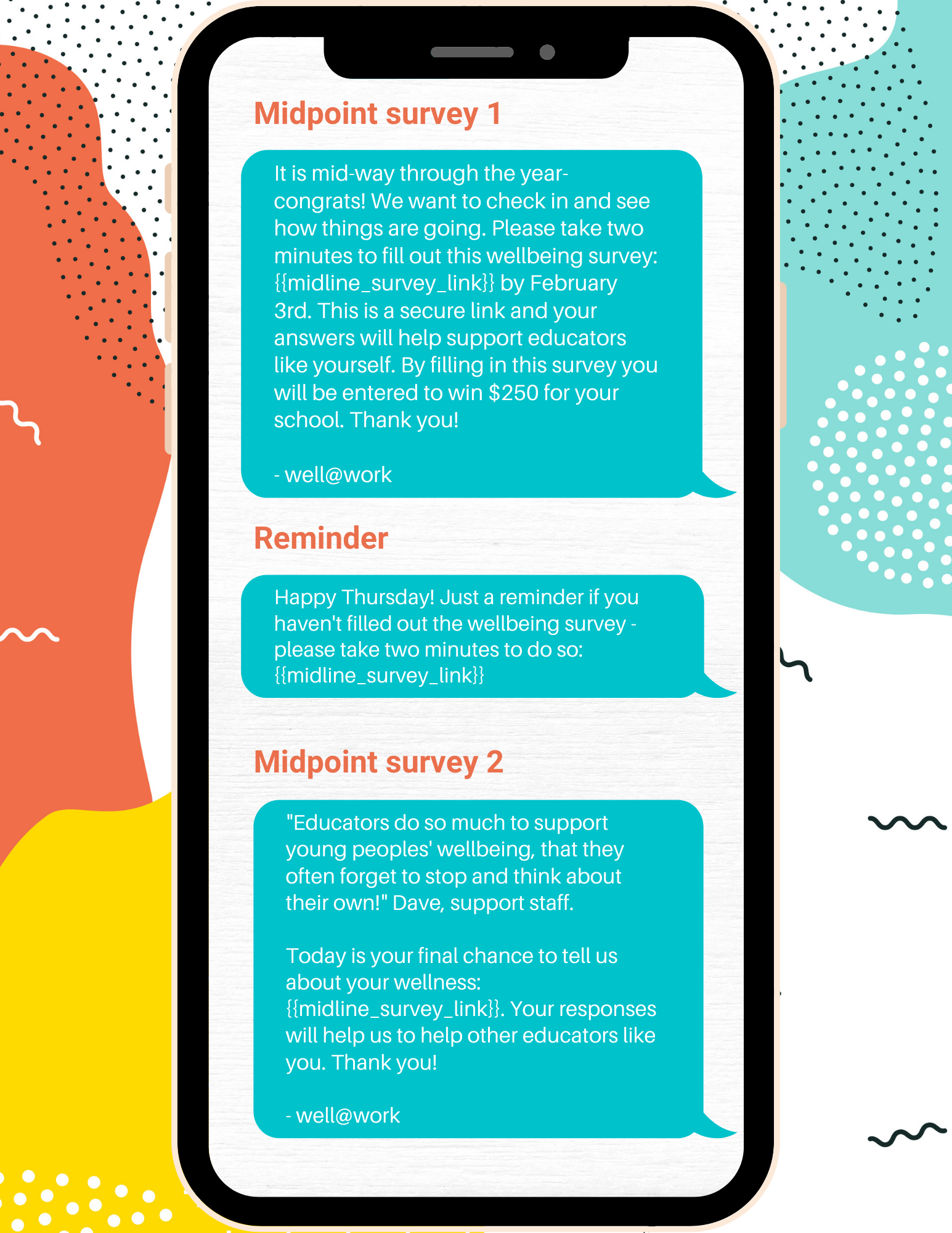

Given the novel approach of this intervention, we rigorously evaluated the SMS and emails, using a randomized experiment taking baseline, midline and endline measurements of wellbeing[2] and burnout[3] for participants in the treatment and control groups. The evidence-based text messages and principal emails were tested in a randomized controlled trial, publication pending.

[2] Wellbeing was measured using the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale [7 items]. Score range: 7~35 (7 = lowest well being, 35 = highest)

[3] Burnout was measured using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory [7 items]. Score range: 0~100 (0 = no burnout, 100 = extreme burnout)

High-level findings and recommended next steps

Our evaluation included two components: qualitative interviews with participants and quantitative data collection. The full evaluation results are embargoed pending peer-review and academic publications, but below we discuss high-level findings, next steps, and future research.

Findings. We found that these text messages on their own were not sufficient to move such stable traits like wellbeing[4] or burnout[5] over a period of 6 months.[6] However, from our qualitative interviews, participants reported enjoying the messages and noted that they served as a reminder to focus on their own wellbeing. Qualitative findings like these highlight potential benefits to participants which may not have shown up in the quantitative results. Importantly, definitive conclusions are difficult to interpret given the emergence and vast impact of COVID-19 during our trial period.

Next Steps. While this trial produced null results, we think there is merit in testing similar light-touch intervention models with some adaptations outlined below:

1.Use SMS as a channel to connect staff to resources and share wellbeing strategies

- Increasing uptake of mental health resources through SMS. SMS may serve as a good way to reinforce and increase uptake of existing, more intensive services (e.g., counselling, Employee Assistance Programs).

- Consider sending timely reminders to engage in helpful practices, as described in this report. Mobile phone SMS message reminders have been shown to enhance healthy behaviour from smoking cessation to meds adherence.[xlii]

2. Use peer-to-peer messaging

- Messenger effect. People are more receptive to messengers that come from sources who are demographically similar to them.[xliii] While our trial sent messages from “well@work”, future trials should consider using a more relatable messenger, such as a fellow educator.

- Normalizing wellbeing behaviours. People are heavily influenced by the behaviours of their peers. If peers send messages or encourage prioritizing wellbeing behaviours it may be more likely to become a social “norm” for the rest of school staff.

3. Refine and prioritize leadership messages. Future light-touch wellbeing strategies should maintain a strong focus on leadership communications.

- Personalization. People respond better to stimuli that is personalized (has their name, information specific to them, etc.).[xliv] From our qualitative findings, principals reported positive responses from our pre-written emails when they took the time to adapt to their own school culture.

- Role modeling. Leadership behaviour has been found to influence staff wellbeing.[xlv] Leadership emails can serve as a way for principals to highlight the ways they prioritize their own wellbeing – making it more acceptable for staff to follow their lead.

Future research. We recommend future research in this area test the combination of these light-touch, low-cost interventions along with larger systemic changes (e.g., reducing workload, smaller class sizes, etc.) to understand the potential impact.

Given the stability of wellbeing and burnout over time, more sensitive measurement tools should be used and employed with greater frequency. Additionally, including student outcomes in future trials would help us better understand the potential impact of staff interventions on students.

This trial represents a novel application of behavioural science to complex topics like burnout and wellbeing. As the field of behavioural science expands, it is imperative to continue conducting rigorous evaluations, such as this, to understand the promises and limitations of the field.

[4] as measured by Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale

[5] as measured by the 7-tem Copenhagen burnout inventory

[6] For our analysis we used the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). Both these scales are well validated and widely used in the field. However, when looking at the questions asked in both the SWEMWBS and CBI, the questions being asked are measuring stable traits that are difficult to move over time – making it difficult to detect subtle changes to wellbeing or burnout. In the future we would recommend using a combination of wellbeing and burnout measures and increasing the frequency of measurement to see if we can detect even small fluctuations over time.

About the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT)

The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) generates and applies behavioural insights to inform policy, improve public services, and deliver positive results for people and communities. BIT works in partnership with governments, local authorities, businesses and charities, often using simple behaviour changes to tackle policy.

Emily Larson

email: emily.larson@bi.team

Emily is a Senior Advisor at BIT North America. While at BIT London, Emily led the schools and wellbeing brief. Emily has worked on reducing burnout, increasing parental engagement and using edtech to reduce teacher workload. Before joining BIT, Emily was the director of an international organisation that brought together leaders in the fields of education, policy and psychology.

Meet the Knowledge Mobilization team at Well at Work

André Rebeiz, Research Manager

André is Project Lead for EdCan’s Well at Work initiative, which supports school districts and provinces to make teacher and staff well-being a top policy and investment priority. He is a graduate of Sciences Po Paris (Institut d’études politiques de Paris) holding a Master’s degree in International Public Management from the Paris School of International Affairs and a Bachelor’s degree in the Social Sciences.

Sarah Ranby, Research Analyst

Sarah leads the planning, communications, coordination, and conducting of research and knowledge mobilization outputs for EdCan. She earned her Master of Science Degree in Family Relations and Human Development and holds a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Psychology from the University of Guelph. Sarah’s research interests broadly include knowledge mobilization, and program evaluation, in particular, analyzing school-based supports that promote positive mental health.

Additional templates for use during COVID-19

SMS during COVID-19 Template Booklet

Email during COVID-19 Template Booklet

References

[i] Hallsworth, M., & Kirkman, E. (2020). Behavioral Insights. MIT Press.

[ii] Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational psychology review, 30(2), 373-396.

[iii]Coolie, R.J., Shapka, J.D., and Perry, N.E. (2012). School Climate and Social–Emotional Learning:Predicting Teacher Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Teaching Efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4):1189 –1204

[iv]Wang, F., Pollock, K., and Hauseman, C. (2018). School principals’ job satisfaction: The effect of work intensification in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 185:73-90

[v]Pollock, K., Wang, F., & Hauseman, D. (2017). The changing nature of vice-principals’ work. Final Report. Ontario Principals’ Council, Toronto, ON., Canada.

[vi] Froese-Germain, B. (2014). Work-Life Balance and the Canadian Teaching Profession. Canadian Teachers’ Federation. Retrieved from http://www.ctf-fce.ca/Research-Library/Work-LifeBalanceandtheCanadianTeachingProfession.pdf

[vii]Burke, R., Greenglass, E., and Schwarzer, R. (1996), Predicting teacher burnout over time: Effects of work stress, social support, and self-doubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 9(3):261-275.

[viii]Darr, W., and Johns, G., (2008). Work Strain, Health, and Absenteeism: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 13:293-318.

[ix]Miller, R., Murnane, R., and Willett, J. (2008). Do Teacher Absences Impact Student Achievement? Longitudinal Evidence from One Urban School District. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 30(2): 181-200

[x]Molero Jurado, María Del Mar & Pérez-Fuentes, María & Atria, Leonarda & Oropesa Ruiz, Nieves Fátima & Gázquez Linares, José. (2019). Burnout, Perceived Efficacy, and Job Satisfaction: Perception of the Educational Context in High School Teachers. BioMed Research International: 1-10.

[xi] Núñez, Juan & Sarmiento, Celia & León, Jaime & Grijalvo, Fernando. (2015). The relationship between teacher’s autonomy support and students’ autonomy and vitality. Teachers and Teaching, 21: 191-202.

[xii] Oberle, Eva & Schonert-Reichl, Kimberly. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine. 159:30-37.

[xiii] Briner, R.B. & Dewberry, C. (in partnership with Worklife Support) (2007). Staff well-being is key to school success. Retrieved 14 June 2019, from: http://www.worklifesupport.com

[xiv] Harding, S., Evans, R., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., … Kidger, J. (2019). Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? Journal of Affective Disorders, 242: 180-187

[xv] McLean, L., & Connor, C. M. (2015). Depressive symptoms in third‐grade teachers: Relations to classroom quality and student achievement. Child Development, 86(3), 945-954.

[xvi] Hoglund, W. L., Klingle, K. E., & Hosan, N. E. (2015). Classroom risks and resources: Teacher burnout, classroom quality and children’s adjustment in high needs elementary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 53(5), 337-357.

[xvii] Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4-36.

[xviii] Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine, 159, 30-37.

[xix] Jennings, P. A., Brown, J. L., Frank, J. L., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Davis, R., DeMauro, A. A. & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). Impacts of the CARE for Teachers Program on Teachers’ Social and Emotional Competence and Classroom Interactions. American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000187

[xx]Roeser, R. W., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Jha, A., Cullen, M., Wallace, L., Wilensky, R., … & Harrison, J. (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105:787–804.

[xxi] Schutz, P. A., & Zembylas, M. (Eds.). (2009). Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives. New York, NY: Springer

[xxii] McCarthy, C. J., Lambert, R. G., Lineback, S., Fitchett, P., & Baddouh, P. G. (2016). Assessing teacher appraisals and stress in the classroom: review of the classroom appraisal of resources and demands. Educational Psychology Review, 28:577–603.

[xxiii] Unterbrink, T., Pfeifer, R., Krippeit, L., Zimmermann, L., Rose, U., Joos, A., & Bauer, J. (2012). Burnout and effort–reward imbalance improvement for teachers by a manual-based group program. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85:667–674.

[xxiv] https://www.bi.team/blogs/why-text/

[xxv] https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00266?gko=0540c

[xxvi] https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00266?gko=0540c

[xxvii] Grant, A. M., Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude motivates prosocial behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

[xxviii] Gollwitzer, P. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist 54(7), 493-503.

[xxix] Chang, Y.-P., Lin, Y.-C., & Chen, L. H. (2012). Pay it forward: Gratitude in social networks. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being.

[xxx]Catherine Brozena. (2018). How Gratitude Can Reduce Burnout In Health Care.

[xxxi] Hülsheger, Alberts, Feinholdt, & Lang, 2013. https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/sites/default/files/documents/Mindfulness%20and%20Work%20Hulsegher%202013%20.pdf

[xxxii] Lomas, T., Medina, J.C., Ivtzan, I. et al. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Well-Being of Healthcare Professionals. Mindfulness, 10, 1193–1216.

[xxxiii] S. Cohen, B.H. Gottlieb, L.G. Underwood, Social relationships and health, in: Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists, Oxford University Press, USA, 2000, pp. 1–25.

[xxxiv] Park JO, Jung KI. (2016). Effects of Advanced Beginner-Stage Nurses’ Sense of Calling, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment on Retention Intention. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2016 Mar;22(2):137-147.

[xxxv] Timothy Bartram, Therese A. Joiner & Pauline Stanton (2004) Factors affecting the job stress and job satisfaction of Australian nurses: Implications for recruitment and retentionhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5172/conu.17.3.293, Contemporary Nurse, 17:3, 293-304, DOI: 10.5172/conu.17.3.293

[xxxvi] Timothy Bartram, Therese A. Joiner & Pauline Stanton (2004) Factors affecting the job stress and job satisfaction of Australian nurses: Implications for recruitment and retentionhttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5172/conu.17.3.293, Contemporary Nurse, 17:3, 293-304, DOI: 10.5172/conu.17.3.293

[xxxvii] Linos, E., Ruffini, K., & Wilcoxen, S. (2019). Reducing Burnout for 911 Dispatchers and Call Takers: A Field Experiment (No. 1158). EasyChair.

[xxxviii] Koenig, A. (2014). Learning to prevent burning and fatigue: Teacher burnout and compassion fatigue.

[xxxix] Park, Y., Fritz, C. & Jex, S.M. Relationships between work-home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: The role of communication technology use at home. J. of Occ. Health Psych. 2011, 16(4), 457-467.

[x1] Hultell, D., & Gustavsson, J. P. (2011). Factors affecting burnout and work engagement in teachers when entering employment. Work, 40(1), 85-98.

[x1i] Erin wt al. (2014). Changing Work and Work-Family Conflict: Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network. American Sociological Review. Vol 79, Issue 3

[xlii] Orr, J.A. (2014). Mobile phone SMS messages can enhance healthy behaviour: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychology Review, 9(4), 397-416.

[xliii] Cabinet Office & Institute for Government (2010). MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy.

[xliv] Haynes, L., Service, O., Goldacre, B., & Torgerson, D. (2012). Test, learn adapt: Developing public policy with randomised controlled trials. Behavioural Insights Team, Cabinet Office.

[xlv] Van Dierendonck, D., Haynes, C., Borrill, C., & Stride, C. (2004). Leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. Journal of occupational health psychology, 9(2), 165.